As anyone who has ever tried to name a band or a theatre company or a novel will confirm, naming can be a tricky process. While the phrase dharma noir has a nice ring to it, the sounds that appeal to the ear often convey meanings that are reductive or difficult to justify. I am intrigued, though, by the case that can be made for how a Buddhist meditation practice resonates with the noir tradition in pulp fiction and popular film that arose in the mid 20th century and that continues today in various forms. The typical story of an individual’s progress along the path of dharma takes a narrative form with strong noir overtones. And the promise of transformation entailed by Gautama’s awakening beneath a tree in the forest entails a paradoxical kind of hopelessness that is a core attitude of film noir.

Even Buddhism’s origin story dovetails in surprising ways with the basic arc of a film noir. Growing up, the young prince catches glimpses of a villain operating from the shadows at the center of the world. In the lives of the poor and in the bodies of the dead and dying the evidence of this villain’s invisible, pervasive malice is especially clear, and yet no one else seems to perceive his influence. Disturbed by the destructive power of this elusive criminal, the young prince leaves home to track his opponent to his lair. In the company of mendicants and wise men, our princely detective hones his analytical skills, overcoming many obstacles. Finally, at the end of the night, he is ready. Sitting beneath a tree in the forest, he summons his opponent. This opponent—let’s call him Mara—brings to this encounter all of his mechanisms of seduction and coercion. He threatens and cajoles, offering the prince astonishing riches and even, it is said, his three beautiful daughters (their names were Thirst and Discontent and little Greed). Like Christ tempted by Satan in the desert, the prince refuses each of these enticements. Then, as he touches the earth with his right hand, the opponent’s essential emptiness is exposed to the light, and an entirely new mode of being enters the world.

Centered around issues of crime and punishment, film noir does not amount to a strict genre so much as a collection of attitudes, postures and motifs expressing what Marxist scholar Raymond Williams called “a structure of feeling.” The psychology of sin and transgression in iconic noirs such as Double Indemnity or The Postman Always Rings Twice raise up what the Jungians call shadow—those aspects of ourselves deemed to be deficient or shameful are repressed in the psyche and pushed from awareness. This kind of splitting of ourselves into parts we want to see and parts we disown is the source, modern psychology tells us, of various forms of neurotic projection and dysfunction. Relegated to the subconscious, those disowned aspects of ourselves remain active, shaping our behavior in covert and not-so-covert ways—the famous “return of the repressed.” Though always performed in the name of the good, this kind of violence against who we truly are ultimately fuels the vast traumas characterizing the first half of the 20th century—the two world wars. Better for everyone if we integrate those aspects of ourselves instead of projecting them onto others, and this challenging process entails reorganizing the internal dynamics of our psyche. Film noir speaks to that part of ourselves that us curious about the shadow in ourselves and others. We savor the negativity of these films, not despite but rather because of their atmosphere of doom and despair.

I like how the name dharma noir positions issues of shadow front and center in a meditation practice. There are differences, but a correlate to shadow in Buddhist thought is ignorance, the root “poison” that gives rise to desire and aversion. Dharma noir gestures toward Tibetan tanka, for example—those vivid depictions seething with monstrous debt collectors and demons to symbolize the intense friction we encounter when our meditation practice begins to cut into the cables energizing habitual ways of relating to experience. My first teacher, Ken McLeod, emphasized this point, which often gets lost in the urge to evangelize the joy, love and compassion that flow from meditation.

Lately I have found it useful to think of film noir as a narrative mode rooted in the collision between the individual and a system of coercion and control; indeed, with systematicity itself. In some of the films, The Maltese Falcon or The Third Man, for example, we encounter an out-and-out criminal conspiracy. In other film noirs the hero encounters the corrupt power of the social order, as in The Sweet Smell of Success. Sometimes the evil manipulates cultural codes to conceal itself, the way Joseph Cotton’s Uncle Charlie does in Shadow of a Doubt. Often, it is simply the covert power of wealth to corrupt and dominate, as in Polanski’s Chinatown, or the power of the feminine to entrain a man’s will, as in Double Indemnity. Perhaps most often what we encounter in these films is simply the complex web of fate—the hero contending with the raw power of distant causes ripening into current conditions. It is as if Western culture in the 1930s and 40s located a narrative form to bring to light the centrality of systems and systematicity even as that same topic was being formally articulated in the science of cybernetics that arose around that same time. Since much of our contemporary world has been powerfully shaped by the information processing revolution cybernetics ushered in, it makes sense noir would continue to feel relevant today.

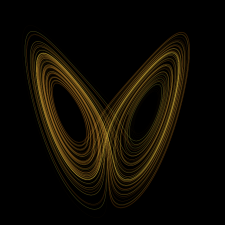

How remarkable that this same concern with liberation from the systematic dynamics of habitual conditioning can also be located in the Buddhist critique of normative human existence. The famous Wheel of Samsara, a central image in many Buddhist traditions, for example, is full of systematicity. In a typical representation, the hub of the wheel contains images of a rooster, a snake and a pig symbolizing the forces of desire, aversion and ignorance. Moving outward, these “three poisons” animate the six separate realms defining the different modalities of experience available to the separate, striving ego. Suffering is ubiquitous across these different realms, but the suffering of each has a distinctive style—the Hell realm is defined by anger, the Hungry-Ghost realm by addictive craving. The Animal realm is characterized by a kind of dull bewilderment, while the God realm features the blindness of pride. Competitive aggression is the central affect of the Titan realm, while a preoccupation with comfort and convenience defines the Human Realm. The endless turning of this “wheel” defines a life of suffering. The aim of Buddhist practice is to wake up from this pointless systemic capture to our natural state of connection, love and compassion—light amid the darkness.

One of the intriguing features of systems is how their dynamics can apply to both the living and the nonliving. Complex adaptive systems such as hurricanes and the stock market, for example, draw to themselves the material, energy and information they need in order to maintain shape and function—this is a version of desire. These systems reject what threatens their continued existence—a kind of aversion—and ignore all else. Viewed through this lens, dharma practice offers us a way to liberate ourselves not just from the social reward system we inherited from our primate forebears, but also from being dominated by systemic dynamics common to us and to the nonliving. To begin to see these dynamics at work in one’s life is a sobering experience, and it helps to be prepared.

On a more associative level, the name dharma noir, finally, points toward many other things I hope to explore in this blog. The Greek tragedies radiate dharma noir, as do so many myths and folk tales back through time. Dharma noir lights up the films of Luis Bunuel along with those of Akira Kurosawa, Robert Bresson and Andrei Tarkovsky. The novels of Thomas Bernhard and of WG Sebald are infused with dharma noir, and so is the work of Samuel Beckett, William Burroughs and Roberto Bolano. The pulp novels of Elmore Leonard pulse with dharma noir, as do those of Patricia Highsmith. Dostoyevsky is a patron saint of the ravishing dark, and Lorca’s duende is, for me, composed of dharma noir all the way down. I have invited other practitioners involved in the arts to contribute to this blog and they will be free to choose what to take up. My only requirement is that posts feature rigor and nuance regarding meditation practice while remaining accessible for those who do not practice directly.