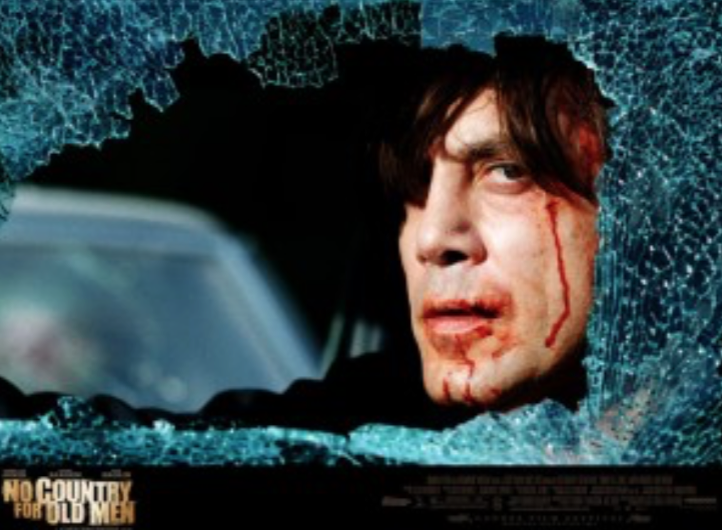

Javier Bardem as Anton Chiguhr

February 13, 2010 | by Guy Zimmerman

That Oscar gold showered down this year on James Cameron’s Avatar, with its connective planetary goddess, says a great deal about how deep a ditch we have dug for ourselves. The central idea of the film, after all, is that while the ruination of our own ecosphere is a done deal there exists, somewhere far far away, a planet where human greed and aggression will finally meet their match. If hope is your cup of tea you might want to look a little closer to home. For that purpose another recent Oscar winner comes to mind – No Country for Old Men by the Coen brothers, based on the noir thriller by Cormac McCarthy. The hope it contains may be on the dark side, but so are the forces that have pushed our world so dangerously out of balance.

In my last post, Theory of Miracles, I wrote about emergence, a concept central to many intriguing developments in the physical sciences. It is a concept expressed in deity figures like the benevolent life force in Avatar. A good candidate for the opposite of emergence, in my view, would be reification. Reification is a fancy word for a kind of collapse we all encounter at various levels of experience throughout the day, and it is central to the culture of materialism. To reify is to reduce a complex process to a static thing, separate and apart, unique unto itself.

If you made a deity figure out of reification (as opposed to emergence) that deity would look very much like the Protestant God of Capitalism. This deity is all about breaking connective bonds (social, psychological, chemical, molecular, atomic, etc…) in order to exploit the energy they contain. And along with the boundless dynamism and creativity that have given us automobiles, moon walks and the small pox vaccine, this God of Thingification has also bequeathed us species extinction, nuclear weapons, and a badly damaged ecosystem. He is the Christian God shorn of the Virgin Mary, who represents that balancing, feminine instinct for staying in touch with Being.

Karl Marx wrote a lot about reification and so, in his own way, did William Shakespeare. Read Shakespeare’s great tragedies and you will find the theme everywhere. King Lear’s root error, for example, is to turn love itself into a thing that a father can demand from his children. And in Macbeth we see the concept of a king get plucked out of the complex web of relationships that supply its meaning and become centered in a thing, a crown, that can be seized by an act of violence.

The process of reification turns every man into a would-be usurper pursuing the tokens of material success. And sure enough, a short time after Shakespeare wrote The Tragedie of Macbeth the king-killer Oliver Cromwell appears on the scene, launching the modern era with his New Model Army.  The various Protestant sects born in the fire of that Civil War left England to settle America, which has become a land of little Macbeths sharpening hidden knives. This kind of thumb-nail history is always tricky, but the fact that we still inhabit the world Shakespeare foreshadowed in his plays explains why Hamlet and Lear remain mainstays of global drama, and why Shakespearean writers such as Cormac McCarthy feel so relevant to our lives. In novels such as Blood Meridian, No Country for Old Men and The Road, McCarthy has been tracking the trends that so worried Shakespeare.

The various Protestant sects born in the fire of that Civil War left England to settle America, which has become a land of little Macbeths sharpening hidden knives. This kind of thumb-nail history is always tricky, but the fact that we still inhabit the world Shakespeare foreshadowed in his plays explains why Hamlet and Lear remain mainstays of global drama, and why Shakespearean writers such as Cormac McCarthy feel so relevant to our lives. In novels such as Blood Meridian, No Country for Old Men and The Road, McCarthy has been tracking the trends that so worried Shakespeare.

One paradox McCarthy loves to illuminate is how desperately the god of reification strives to avoid being reified himself. No god wants to be reduced to just another thing, and especially the “jealous god.” And so he hides, receding into the woodwork of the universe where he masquerades as Natural Law. He is the one-God of Adam Smith and Isaac Newton, the deity of materialism who is difficult to free oneself from because he hides from view where his authority cannot be questioned. And this is where No Country for Old Men, becomes especially interesting.

Buried under the plot of No Country lies a complex meditation about fate, Ananke, karma American style. The hero, Llewelyn Moss commits a series of cosmic indiscretions and the hit man Anton Chigurh is dispatched by our implacable, impersonal deity to make a corpse-thing out of Moss. Moss’ first “error” is failing to kill the antelope he shoots at in the beginning of the film. Some little hesitation, perhaps, ruins his aim and the antelope runs off, wounded. Next comes Moss’ biggest  error – he returns to the scene of a massacre to give a dying man water. Through these errors Moss identifies himself as an apostate in the temple of materialism. His heart is not true – he worships at some other altar. In the domain of the one jealous god this is not okay and Chigurh is sent to “thingify” Moss.

error – he returns to the scene of a massacre to give a dying man water. Through these errors Moss identifies himself as an apostate in the temple of materialism. His heart is not true – he worships at some other altar. In the domain of the one jealous god this is not okay and Chigurh is sent to “thingify” Moss.

In numerous scenes Chigurh presents himself as an agent of “necessity.” In his vanity he refuses to acknowledge that he works in service of a god. And, again, this is fitting because Chigurh serves the god who conceals himself because he wants to be the only god. Hulking around with his pneumatic cow-killing machine, Chiguhr is a demon of the hidden

monotheism that underlies the material view of the world.

After Moss is dead, Chigurh pursues Moss’ innocent wife, Carla Jean. Before taking her life, Chigurh tells Carla Jean he is only enacting a fate Moss himself set in motion for her. Carla Jean scoffs – Chigurh has come to kill her because he likes to kill, plain and simple. No impersonal law is being served. This insight doesn’t gain Carla Jean anything – Chigurh kills her anyway – but driving away he is grievously wounded by a speeding car that appears out of nowhere. What is the meaning of this odd bit of seemingly random violence? The tables have been turned on Chigurh. Either the car slamming into him had no meaning at all – in which case his own acts of violence are equally devoid of cosmic significance – or the car slamming into him represents the intervention of some rival force or energy…in which case the “impersonal law” he claims allegiance to is the expression of one deity among many. Either way, Chigurh is revealed as a creature of delusion. As he hobbles away on his broken bones, we sense that he has been reduced in his own eyes.

violence are equally devoid of cosmic significance – or the car slamming into him represents the intervention of some rival force or energy…in which case the “impersonal law” he claims allegiance to is the expression of one deity among many. Either way, Chigurh is revealed as a creature of delusion. As he hobbles away on his broken bones, we sense that he has been reduced in his own eyes.

As powerful as he is, all it takes to undo the god of materialism is the whisper that he is not, in fact, alone. In McCarthy’s understated, hyper-masculine way what No Country announces is the rebirth of the connective deity that reigns over the planet of Avatar. She is the great emergent rival of the reductive Protestant god, the presence the poet Ted Hughes identified as the “Goddess of Complete Being” in his remarkable book about Shakespeare. In the four centuries since she departed from the scene the world has been transformed. In flight from the mystery of Being we have pulled nature apart to analyze matter and energy down to their smallest components. And there we have discovered…mystery. Particle-wave duality…action at a distance…non-locality…the materialistic exploration of the world has unearthed, not the longed-for certainties, but the most mind-confounding paradoxes ever contemplated. Every time we use a computer, a cell phone, or a microwave oven we are reaching down into a miraculous quantum realm where matter and energy are interconnected in ways we can scarcely comprehend.

And now, having reached the bottom of the world, the scientists raise their eyes…and there she is, clothed in the very real hard science of complex systems and emergent form, like Venus rising up out of the waters…

And now, having reached the bottom of the world, the scientists raise their eyes…and there she is, clothed in the very real hard science of complex systems and emergent form, like Venus rising up out of the waters…

COMMENTS

Lesquery B. says:

February 14, 2010 at 12:25 pm

In arguing that somehow Llewelyn Moss is an “apostate in the temple of materialism,”

Zimmerman conveniently elides the fact that Moss steals two million dollars. Though Moss returns to give the dying man water, his goal throughout the story is to escape with the money and become a rich man. Indeed, Moss is so intent on this capitalist/materialist triumph that he is willing to battle a ferocious killer and jeopardize both his and his wife’s lives. Thus Moss reifies happiness into money, which leads to his downfall. You’ve got the semiotics backward, Zimmerman: Moss is the materialist reifier, while Chigurh is the one delivering punishment to those who worship capital at the expense of life, love, happiness.

Guy Zimmerman says:

February 14, 2010 at 4:43 pm

I simply disagree. Llewelyn wouldn’t work nearly so well if he weren’t close-to-but-not-

quite a believer. It’s not that he wants the money, it’s that he wants the money AND he wants to retain his humanity to boot (by bringing a dying man water). And later he wants to retain the money AND his dignity as a man who-has-been-wronged. That is what is especially unforgivable. You can’t be an apostate if you weren’t first a believer, or claimed to be, in other words.

McCarthy did the same thing with The Kid in Blood Meridian and his relationship to the Judge. The Judge, even more than Chiguhr, is explicitly a creature of the Enlightenment, the scientific mentality. And he kills the Kid in the end because in some subtle way the Kid has strayed from the path of unconditional violence that the deity of that world demands. Having said all that I’m glad the piece kindled a clear and different opinion. That is, of course, partly the point.

Yours, GZ

rachel j says:

February 17, 2010 at 11:01 am

i need to catch up on my movies (!), but still, another wonderfully thought-provoking post that will percolate in my brain for days to come. thanks, Guy!

john steppling says:

February 19, 2010 at 8:29 pm

Zimmerman is right I think (regarding the debate with lesquery). One has to remember

that McCarthy ends the book (and in a truncated way the Cohen brothers do the movie) with a long reflective monologue from the sheriff. The critical point in that near stream of consciousness is that we are all culpable in the destruction — in the violence {this particularly because the sheriff is a, well, sheriff, and in the work of stopping such violence}. This is a theme McCarthy explores over and over. Also, Chigurh is in no way an avenging angel. He is not about punishment….but is rather a projection of our collective guilt, and ..at least in the book……..a figure of unreality. He is not merely a madman, or psycho…..he is rather the lucid dream of our darkest instincts.

Its a complex question, tweezing apart the Biblical tropes in McCarthy — but Zimmerman seems to be suggesting a larger question anyway. The fatalistic aspect in McCarthy is always tied to our shared existence. In Blood Meridian the national crime of the genocide of native americans is the spectre haunting the entire book. Judge Holden is, in many ways, much like chigurh. We cannot escape, for he is us. Moss is treated as a good man, but one who could not escape the collective crime of filthy lucre and its reified power to dominate our existence. Advanced capital if you will. Moss is not seen as a thief…..for such a reductive notion is almost meaningless in a McCarthy landscape anyway. He is a traveler through the ante chamber of hell — one he simply could not escape. His life before the finding of the money was only an extended delaying of his (our) fate.

The sheriff sees this clearly at the end. Resistance on the level of “crime fighting” is futile. Zimmerman approaches this in a fascinating fashion, albeit a bit different than I am suggesting. But the idea that Moss simply wants to be a rich man is rather to miss the bigger points — and to posit some idea that he is jeapordizing his wife is really to miss the point. This isnt a liberal fable about responsibility. That might float in typical Hollywood film, in fact it does. But it is exactly the deconstructing of such causal reasoning that McCarthy is looking at. McCarthy is the heir to Melville and No Country is maybe his finest book in fact.

adam stilwell says:

February 24, 2010 at 5:51 pm

Very radical. really enjoyed this. all these great arguments about ‘No Country’ aside

(that’s what a good movie’s all about anyway, in my humble opinion) your getting at something here. with your ideas of emergence in your last piece ‘Theory of Miracles’ and now your words on materialism and ‘thingafying’ I believe you have a fresh and thrilling view on the current state of human existence. and i really appreciate it.

thanks.